"Inside. Outside. Darkside. Brightside." - Criminology Seminar 2023

LOUPS Criminology Seminar – 11th November 2023

The inevitable train disruption, Remembrance Day commemorations, and a pro-Gaza march on the streets of London could not stop us attending the London Open University Psychological Society’s Criminology Seminar! Back at The Marshall Building at the London School of Economics, we were treated to another outstanding LOUPS event. Our three lecturers were, Mary Haley, Dr Dan Rusu, and Professor David Wilson, who each presented fascinating talks concerning criminological and psychological phenomena.

There won't be recordings from this event as Dan’s book is forthcoming and David is presenting aspects elsewhere but this was a truly sensational event: invigorating, thought-provoking and such a lively, interactive day! If only we could have these wonderful and popular speakers every year. An audience of so many people wanting to learn, understand or who work in the Criminal Justice System, including Dr Liam Brolan, made this Criminology Seminar a day that any society would strive to improve on.

The wonderful lectures were delivered to a rapt audience in a full theatre who shared differing experiences and perspectives. The lectures were standalone yet interconnected with one another. In reflecting on how to report the event, the entanglements, and the primary takeaway from David Wilson about how to make a difference, the emerging themes of Inside, Outside, and Darkside felt an appropriate manner of summarising the seminar.

INSIDE.

Mary Haley opened her second LOUPS event of 2023 with her fantastic talk, "It’s an Inside Job!".

Mary has extensive experience of working in prisons, including HMP Grendon, which is where she is the Clinical Training and Development Manager. Grendon has therapeutic communities in which there is a collaborative paradigm whereby the residents are engaging in psychotherapy in groups and individually. The stark power dynamics of prisons can be problematic to therapeutic interventions. However, Mary noted that while therapy inside prisons can be difficult for such reasons, there are also circumstances in which it is easier. For example, the peer dynamics foster truth because the prisoners challenge one other should someone be evasive or otherwise untruthful. The language used is especially important during therapy inside prisons in that nearly any insult is fine with the exception of to call someone a ‘victim’ or ‘vulnerable, despite the veracity of such statements.

Mary listed a number of issues which impact psychotherapy inside prisons, such as, the history of trauma among the prison population. However, she reiterated the importance of recognising that not everyone who experiences trauma commits violent crime and vice versa. Nevertheless, the prevalence is significant. Other issues include avoidance, rage, and inner conflict. Mary also referenced one of the biggest challenges of delivering therapy inside prisons: there are three people in the relationship. In therapy, there are usually the client and the therapist, who share a mutual understanding of, for example, confidentiality. However, the criminal justice system, is a third person in prison therapy because the content of treatment is recorded in session notes, which are important in parole decisions and risk assessments. Mary acknowledges the difference in quality of reports such that a good report is approximately 18-20 pages. Very brief reports could reflect potential omissions, whereas very long reports could include repetition. Mary noted that the reports can be a ‘gift’ to the prisoner in that it can allow them to better understand themselves. Mary was clear about the importance of keeping an open mind and curious stance in providing psychotherapy inside prisons, and beyond. It is both frustrating and rewarding work but it is vital to ensure that practitioners take breaks and other protective measures.

Mary’s brilliant lecture concluded with a question-and-answer session. “What makes the biggest difference?” Mary answered, “therapy”. The importance of therapy cannot be overstated. Similarly, the importance of early interventions, although Mary noted that there can be issues of accessing services, even when there were more available, such as SureStart. Trust issues and other factors can inhibit engagement. David Wilson, who has a significant working history with Mary, asked about gender. David said that Mary had had the “hardest job” at Grendon, and he questioned the relevance or helpfulness of gender. Mary explained that gender is both a help and a challenge, especially if an early abuser had been female. Other questions included queries about volunteering opportunities and wondering about interventions in young offender populations. Volunteering opportunities are complicated, and prisons are still impacted by Covid-19 among other restrictions, but Open Days and relationships with universities are important. Therefore, lateral thinking and proactivity are key, such as applying for other prison roles to gain experience of that environment. Mary is unaware of therapeutic communities in Young Offender institutes but noted that younger offenders tend to leave Grendon sooner than older ones. Finally, in response to a question about avoiding burnout, Mary emphasised the importance of separating your work from your life and having meaningful support systems.

As an opening lecture, Mary’s talk opened the LOUPS Criminology Seminar in style. She once again delivered an incredible session which provides insight into a very challenging environment while simultaneously acknowledging the difficulties but also the hope that can be found providing psychotherapy inside prisons.

Leaving prison by being released is surely the most hopeful of outcomes, but how is life on the outside after incarceration?

OUTSIDE.

Dr Dan Rusu’s "Life Beyond Murder" was our second lecture of the seminar. Using the MentiMeter website, Dan posed the question, ‘Prisoners laugh in our faces. Prison is not harsh enough to be a true deterrent’. We responded by selecting one of four responses. The numbers shifted as people logged in and responded but the results were approximately:

Strongly agree: 3

Agree: 18

Strongly disagree: 8

Disagree: 29

In a discussion around our responses, we heard from people with each opinion. For example, an audience member who strongly agreed with the statement spoke of their experience working in a prison in which there are inmates actively laughing at staff, as well as attacking staff unpunished. Difficult to hear and unimaginable to experience. On the other side of the responses, a "strongly-disagree" respondent likened incarceration to that of battery chickens whereby would you expect an ex-battery hen to behave in a manner of a non-battery hen? Certainly, an interesting perspective and one which arguably reflects the mortification of the soul (Goffman, 1963).

Dan’s doctoral research was a longitudinal qualitative study in which he interviewed a handful of men who had served life sentences for murder. As Dan states, ‘murder is irreparable’, and some of those in prison have the paradox of having killed a person they had loved. Dan’s interviewees came from different backgrounds and included those who had murdered a loved one, those who had murdered for financial gain, and a random homicide. Life in prison necessitates adaptation to survive, whether by primitive behaviours of denial, or maladaptive adaptations, such as self-harming. Dan’s study took a qualitative, narrative approach which included both ethical and practical concerns, but Dan and his interviewees adapted, building mutual trust with the resulting work being incredible. We eagerly await his book!

Consumer culture is something of which we often take for granted. Whether we are immune to its vulnerability-vipers or guilty of buying things to try to feel better [GUILTY! – CCW], it is something we are surrounded by in daily life. However, upon release from prison, Dan’s interviewees were exposed to a truly new world, for example, the Smartphone culture. Dan mentioned feelings of the fear of missing out [FOMO], comparison culture, and the shame of being certain age but only having X car or Y clothes. Consumerism can substitute fragile identities post-release, but economic constraints can complicate the ability to both partake and decline. There are so many conflicting aspects of the post-incarceration experience. An attendee asked Dan whether what his participants said matched. Dan thoughtfully answered that typically this is the case, however, he is not searching or interested in an objective truth, rather in how the individuals themselves understand it.

Dan’s Q&A session encompassed many of the themes within the talk. Identity was one of the greatest and was transitive such that it evolved from material things to more spiritual aspects. A question about self-flagellation in which ex-prisoners work with offenders to maintain their connection to punishment whilst simultaneously helping people was reflected upon by Dan as an interesting hypothesis, however, one cannot generalise from small sample groups. On the other hand, redemption is a theme which has emerged. The relationship between Dan and his interviewees was delicate and Dan reflected on being cautious of the importance of maintaining communication and engagement, while being afraid of being transactional. Dan stated while he does not know if the interviewees were self-reflective at all points of the interviews, he could have potentially represented a vehicle of redemption.

This was a fantastic talk and a perfect second lecture coming after Mary and before David. Dan provided insightful and powerful quotes from his interviewees, his experiences with working with this population, and the courage of one’s conviction [no pun intended!]. For example, David had wanted Dan to use a particular book in his study, but Dan declined: there is an interest in what people do not say. Dan and Liam were David’s final two PhD students, and he could not have chosen better!

DARKSIDE.

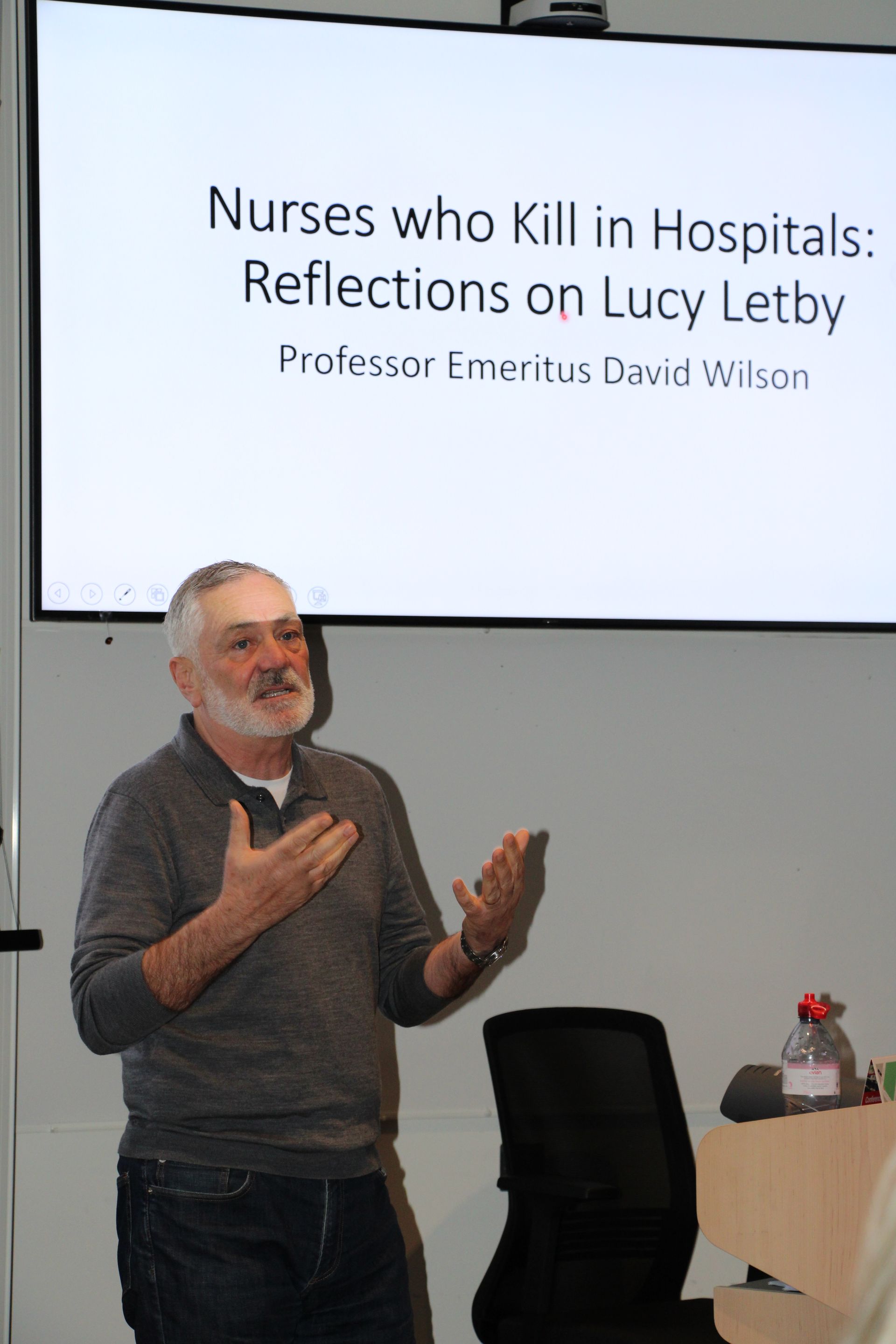

Professor David Wilson closed the conference with his talk: "In search of the Angels of Death". David is connected to both Mary and Dan, as well as Liam, and spoken for LOUPS some years previously, and this time Amada had asked David to present given the high-profile case in the UK recently involving ‘killer nurse’ Lucy Letby. David established his extensive history working with and speaking to those who have committed violent crime, stating that everything he has learned about violent crime came from listening to those who had committed such offences. The juxtaposition of a serial killer being a healthcare worker captures attention and fear among society. David delivered a brilliant lecture to a rapt audience on a topic which cuts to the core: "being unsafe in caring contexts".

The term health care serial killers (HCSK) lacks a precise definition. For example, it has been used to capture any of those working in healthcare positions: clinical and nonclinical. Conceptions have also been highly gendered, with even ‘Angels of Death’ carrying a "[female] Angels" sub-text. David clarified that such killers are extremely rare as the vast majority of healthcare workers care about people. However, the scale of the damage in societies caused by HCSKs is so large that they have over-bearing impact on public perception. Traits have been added to a ‘checklist’ of characteristics, but caution must be exercised because correlation is not causation: innocent people have been convicted. Aside from convictions, motivation is a key topic of interest relating to HCSK, but motivation is not something that the killers David has encountered have often touched upon. Moreover, can you trust them even when they say something? Some killers have spoken at length but really said nothing or say what they think the other person wants to hear. Beware!

Not "nice Lucy Letby?!" Beige, unassuming nurse Letby is an interesting case for HCSK as she both fits with some of the ‘checklist’ factors while also being an outlier in other factors. David reflected on how there is often a stereotype of a killer being one thing, when in fact they are often contrary, or boring and unassuming, for example, Family GP, Harold Shipman and 'The ‘banality of evil’ noted by Hannah Arendt. He noted that there are aspects of the Letby case for the defence which may well yet be further explored, even though these were available throughout the trial. David reminded the audience that Lucy Letby is appealing the current judgements and that there are other investigations ongoing, and that more evidence regarding HCSK may yet emerge in this case and others.

The Q&A session following David’s talk was wide-ranging and thought-provoking, centering on the question of whether there is a link between the means of killing available in healthcare settings which are not available to others and the outcomes in terms of serial killings. Conclusions included the observation that it is important to consider 1. Access, 2. Opportunity, and 3. Motive, when looking at killers. Access and opportunity would be available to many healthcare practitioners who do not kill. There are institutional and structural considerations too, such as burnout. There are people leaving the healthcare professions torn apart. Examples were not lacking in our group alone. David spoke about the investment that is made in incarceration and punishment but not in rehabilitation. A sobering reality of mismatched priorities.

BRIGHTSIDE?

Mary, Dan, and David presented an incredible program of talks for the LOUPS Criminology Seminar 2023. Criminological insight from inside the prison system, outside the prison context, and the shocking dark side of humanity in which criminals can instil fear in wider society. However, this was not the whole day.

There is a Brightside within the darkness. Premature and needing high-level care at a time where the Letby case was everywhere, David recalled watching everything and everyone caring for his newly-born grandson when in hospital care. The doctors and nurses are the reason David beamed ear-to-ear talking about his grandson. David affirmed that his talk was not about Letby. A fellow premature baby shared their triumph after a difficult start, and we all learned that you don’t mess with Brooklyn! Finally, David made a passionate argument that there are things we can do to tackle the violent crime in society: have safe and legal sex work; challenge homophobia; challenge the assumptions of the elderly as a burden not an asset, and have honest conversations about masculinity. We can all do something.

A massive thank you to Mary, Dan, and David for a fantastic seminar. And thank you to Liam for his included work, his book stall toil, and good nature when used as a sartorial example! Thanks to Amada, David, and Sonya for organising and hosting this wonderful event.

Follow LOUPS on all platforms, follow on EventBrite, and sign up to the mailing list (event details only, no spam) for news on future events. Advice is to book early as this event sold out and then refunded tickets were snapped up too!